1989 was an important year. In May of 1989, Yonehara et al. published a report that treatment with an anti-FAS antibody leads to the death of cells expressing our ominously-named gene-of-the-week, “Fas cell surface death receptor” (FAS).1 In July of 1989, Bernhard Trauth and other members of Dr. Peter H. Krammer’s lab described “apoptosis antigen 1” (APO-1) that, when bound by a monoclonal antibody (anti-APO-1), triggers the extrinsic apoptotic pathway, leading to rapid tumor regression.2 And in November of 1989, I was born.

A few years later, in 1992, the Krammer lab revealed that FAS and APO-1 are the same gene!3 Confusingly, FAS/APO-1 also goes by the names “cluster of differentiation 95” (CD95) and “tumor necrosis family receptor superfamily member 6″ (TNFRSF6). Despite its multiple identities, however, all versions of FAS seemed to be doing the same thing—inducing apoptosis. But also in 1992, foreshadowing the future of Krammer’s beloved gene, a brief LA Times article revealed that “Leading a Double Life Is More Common Than Many Suspect.”

It wasn’t until 2004 that the lab of Dr. Marcus E. Peter reported that “CD95” had been leading a double life! 4 During the 90’s, it was discovered that, unexpectedly, most tumors were resistant to CD95-induced cell death. The cause of this resistance was unknown and, because most labs had been focused on CD95’s role in apoptosis, they never guessed that it was involved in its own sabotage… Barnhart et al. from the Peter Lab, however, discovered that CD95 has non-apoptotic functions, and can in fact increase the motility and invasiveness of apoptosis-resistant tumor cells! Although this was shocking to discover, APO-1/FAS/CD95 scientists didn’t walk out on their gene and instead embraced the new path of investigation.

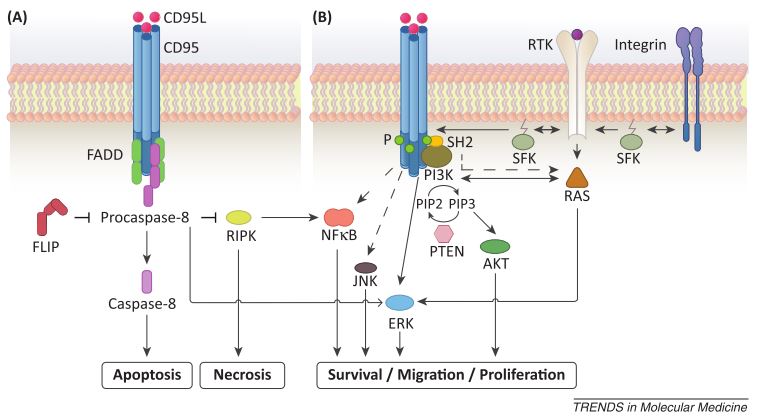

Divergent CD95L-induced tumor responses. (A) CD95L-induced apoptosis can occur through FADD recruitment and caspase activation, which inhibit programmed necrosis. (A) Tumor- or stroma-derived CD95L (either membrane-bound or soluble) can trigger protumorigenic responses, including survival, proliferation, and migration, through ERK, JNK, NFkB and PI3K. (From Martin-Villalba et al, 2013)

Since 2004, both apoptotic and non-apoptotic functions of APO-1/FAS/CD95 have been investigated comprehensively, but the mechanisms of and relationships between the two are still poorly understood. 56 Elucidation of the switch between apoptotic and non-apoptotic functions may someday permit the use of both sides of the double-edged CD95 sword: promoting the apoptotic functions and blocking the non-apoptotic activation in tumor cells.

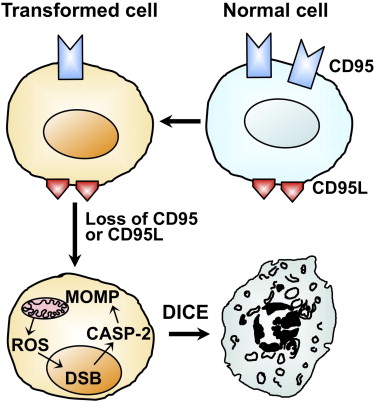

Alternatively, the Peter lab suggested “death induced by CD95R/L elimination,” or DICE, as a promising method for tumor elimination. 7 Hadji et al. used small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) or lentiviral small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) to knockdown CD95 or its ligand CD95L in 15 different tumor cell lines, and both methods led to cell death via an increase in cell size, production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, and DNA damage. Importantly, none of the tested inhibitors of apoptosis, necrosis, mitochondrial integrity, ROS, or their combination completely blocked DICE. This suggests that DICE can be a powerful anti-cancer tool that would be difficult for the tumor cells to resist.

In 1989, no one would have guessed that eliminating the pro-apoptotic APO-1/FAS receptor would be a viable cancer treatment. May this story serve as a reminder to be observant and to expect the unexpected. After many years of inexplicably failed experiments and frustration, you may discover that your genes are doing something totally unexpected behind your back, and it will be great! <3 Science

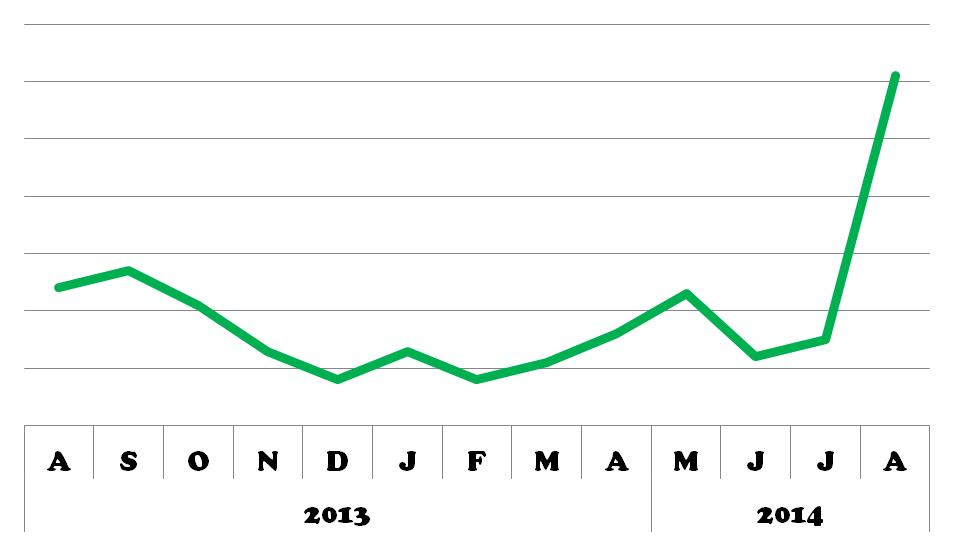

APO-1/FAS/CD95 popularity recently increased, perhaps as a result of the publication of several reviews and Hadji et al.’s DICE findings this year.

References:

- Yonehara, S., Ishii, A., and Yonehara, M. (1989). A cell-killing monoclonal antibody (anti-Fas) to a cell surface antigen co-downregulated with the receptor of tumor necrosis factor. J. Exp. Med. 169, 1747–1756. [↩]

- Trauth, B.C., Klas, C., Peters, A.M., Matzku, S., Möller, P., Falk, W., Debatin, K.M., and Krammer, P.H. (1989). Monoclonal antibody-mediated tumor regression by induction of apoptosis. Science 245, 301–305. [↩]

- Oehm, A., Behrmann, I., Falk, W., and Pawlita, M. (1992). Purification and molecular cloning of the APO-1 cell surface antigen, a member of the tumor necrosis factor/nerve growth factor receptor superfamily. Sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 10709–10715. [↩]

- Barnhart, B.C., Legembre, P., Pietras, E., Bubici, C., Franzoso, G., and Peter, M.E. (2004). CD95 ligand induces motility and invasiveness of apoptosis-resistant tumor cells. EMBO J. 23, 3175–3185. [↩]

- Martin-Villalba, A., Llorens-Bobadilla, E., and Wollny, D. (2013). CD95 in cancer: tool or target? Trends Mol. Med. 19, 329–335. [↩]

- Fouqué, A., Debure, L., and Legembre, P. (2014). The CD95/CD95L signaling pathway: A role in carcinogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1846, 130–141. [↩]

- Hadji, A., Ceppi, P., Murmann, A.E., Brockway, S., Pattanayak, A., Bhinder, B., Hau, A., De Chant, S., Parimi, V., Kolesza, P., et al. (2014). Death induced by CD95 or CD95 ligand elimination. Cell Rep. 7, 208–222. [↩]

Trackbacks/Pingbacks